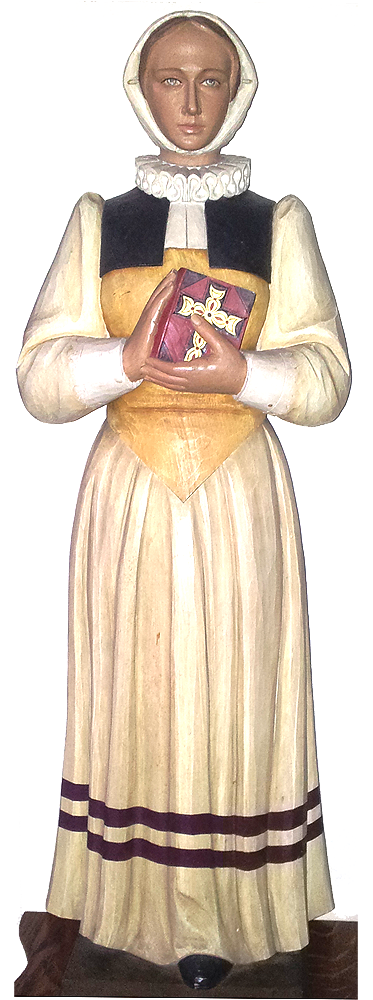

Margaret Middleton was born in York in 1556, shortly before the accession of Elizabeth I. Her father, Thomas Middleton, was sheriff of the city. Brought up in the newly established faith of England, the fifteen-year-old Margaret married John Clitherow, who made a prosperous living as a butcher in the city. They settled in the Shambles, a street unaltered to this day and one of the best preserved medieval streets in Europe. John Clitherow was devoted to his wife and was reported to have said of her that ‘she was the best wife in all England’. They had three children, two boys (Henry and William) and a girl (Anne).

Margaret Middleton was born in York in 1556, shortly before the accession of Elizabeth I. Her father, Thomas Middleton, was sheriff of the city. Brought up in the newly established faith of England, the fifteen-year-old Margaret married John Clitherow, who made a prosperous living as a butcher in the city. They settled in the Shambles, a street unaltered to this day and one of the best preserved medieval streets in Europe. John Clitherow was devoted to his wife and was reported to have said of her that ‘she was the best wife in all England’. They had three children, two boys (Henry and William) and a girl (Anne).

The Elizabethan age was steeped in the tension and intrigue brought about by England’s religious separation from Rome. About three years into married life, Margaret Clitherow was to make a fateful decision to convert to an outlawed faith, to Roman Catholicism, apparently under the influence of prominent York Catholics, the Vavasours. Immediately this put John, her husband, in difficulty because, notwithstanding his love for his wife and possible recusant sympathies, he had official responsibility for reporting signs of Catholic life and worship to the new church authorities.

For all that, Margaret soon became a central stay in supporting Catholic recusancy in a hostile time. She created a secret room in her house in Shambles as a refuge for Catholic priests. She herself suffered imprisonment in 1577 for refusing to attend the religious services of the newly established faith. Resourceful as ever, she did not put months of incarceration to waste, learning to read while in prison. At length though, things were to take a darker turn. After a raid in March 1586, the authorities pressed a frightened, sickly boy into revealing the location of the secret place for priests, and for vestments and the like in Margaret’s house.

When her trial took place in the Guildhall, Margaret refused to plead, thereby preventing the call as witnesses of her children and other loved ones and thus any possible implication of these in her activities. She was therefore condemned to die peine forte et dure – to be pressed to death. “God be thanked, I am not worthy of so good a death as this”, she said.

On Friday, March 25 1586, Margaret was taken to the toll-booth on Ouse Bridge and pressed to death under seven or eight hundredweight. In the fifteen agonising minutes before she died, Margaret cried out “Jesu! Jesu! Jesu! have mercy on me!” A relic – Margaret’s right hand – is preserved in a convent in York. Her sons Henry and William became priests, and her daughter Anne became a nun. Her lovely disposition, her gentle forthrightness against accusation and the sympathy attendant on so gruesome a death have earned her the epithet: ‘Pearl of York’.

Margaret Clitherow was canonized in October 1970 as one of the 40 English martyrs. In England, she shares a memorial on August 30th with two other English female martyrs, Ss Anne Line and Margaret Ward.